I recently had the opportunity to spend time with the Vive team in Seattle. While Vive remains a part of HTC, it has distanced itself from the somewhat beleaguered phone maker and is carving out its own niche in gaming and corporate training. Like Samsung and other early entrants to the “resurgent” VR market, HTC understands that the mass-market appeal of VR remains years away. But they also know that many corporations have found value in training, engineering, and other enterprise applications. So they shifted Vive’s emphasis to the enterprise.

Unlike previous Vive encounters where I climbed Yosemite’s El Capitan (never put a person with acrophobia in a simulation that includes falling down a mountain) or shooting down incoming aliens, this briefing focused on corporate training in a variety of situations from public speaking practice, to safety orientation and practice, to mechanical procedures.

Ovation Public Speaking Experience

Ovation’s public speaking training reflected an offer that most aligned with my personal needs, and therefore resonated most as a value proposition. I could see myself practicing presentations in the Ovation virtual space. I could also see the metrics helping me deliver more consistent presentations when that was called for, be it multi-city product introduction or a thought leadership talk on the future of education.

The experience owner configures the room: the audience mix, the pace of the text feed, what you are holding. Want draw? Add a whiteboard or chalkboard. Vive eye-tracking captures data for feedback on audience contact (do you just stare at one point in space, do you actually look at people in the audience). The controllers track hand movement and offer feedback on gestures during the talk.

The demo consisted of me giving a John F. Kennedy speech on space at Rice University. I put on my best Kennedy impersonation and plowed through the text. I was informed it was the most sustained demo effort the team had seen to date, and the one with the least hums and haws.

The system pointed out that because I was focused on the teleprompter, I didn’t wander through the audience making my gaze count, and I didn’t use my hands very well.

In my experience, the ability to look at an audience and away from the content is a result of repetition. Practicing a presentation leads to memorization of at least key points, which then permits speakers to look around during those key points. That’s one of the tricks of presenting: making eye contract during particularly emotional portions of a presentation.

As for the hand gestures, that comes more from the dissonance, and somewhat awkwardness of the virtual reality experience.

Fire: Safety First

The second experience put in a fire evacuation training situation. I had to remember how to get out safely: low to the ground, look for signs of fire before opening a door, etc.

It was a good use case for basic safety training. Of the three, it was the least memorable. I hope people who work for the company that built it remember their training better than I do.

Construction: Hanging on a String

Imagine you are going up on the steel frame of a hi-rise under construction. One false step…and well, you find yourself hanging on a string with a carabiner tightly locked around some study piece of cold-rolled steel. Or not, and you fall to your death.

This simulation was designed to make sure construction workers who lost their footing experienced the former rather than the latter.

This one took a while and I had a few frustrations along the way. First, the simulation made sure I knew how to use the simulation. Then a lot of repetition and extension. Identify a thing. Put on a thing (mask, vest, pads, gloves, ropes, etc.).

Safety on the Orient Express

I wasn’t exactly sure why I was securing a door on a train, but by g-d, I was going to secure that door. Safety bypasses, wrenches and acute observation. I had to transport myself inside and outside of the car to look for obstructions and clearances. The whole, I can walk but I can’t walk there this is a little disorienting but once you get accustomed to teleporting, it does become second nature. Unfortunately, it may set expectations for real-world teleportation that the real world can’t meet.

The biggest issue with this simulation was the wrench holding action, as holding a controller is not holding a wrench. The weight, the effort, the torque isn’t there.

Evaluating the Vive VR experience

From the start, it was heavy. Perhaps if you own a headset eventually you get it to fit you just right, like a multi-adjustable seat in a car. Unlike most cars, however, VR headsets don’t ship with memory buttons that adhere them to the shape of your skull with the push of a button (but perhaps they should).

I’ll talk to the hardware and software experience directly below, but here I want to concentrate on what VR did and didn’t do well.

What VR did well

Every app created an adequate framework for its intended audience. They captured the essence of what it meant to be in another situation. They attempted to place my focus in the moment even though they didn’t always achieve that goal. All the demos were successful at tracking movement, rendering in realtime (though the models were highly simplified to accommodate this) and accepting input when given.

The plots, or guidance, got me where I needed to go. I learned, I answered questions correctly (most of the time) and when I was wrong, I did not die but was simply visually nudged toward the right answer.

VR also continues to uniquely offer immersive spaces that add a sense of realism to experiences that likely translate into improved retention.

All of the experiences were delivered in enterprise quality. No noticeable glitches that weren’t introduced by VR as the choice of platform (see What VR didn’t do so well below).

Looking back at all the demos, adequate for their purpose emerged as the common thread woven throughout. When corporate investments and key performance indicators drive development for improved safety or reduced costs, adequate often becomes the benchmark.

What VR didn’t do so well

So perhaps the hype chimes continue to ring in my ears—but I wanted more: better rendering, less intrusive hardware and a more refined mapping between me and the VR experience. And…

…VR seriously needs voice control. With a limited number of commands, launching and navigating could be improved. People are isolated in VR, but not in the real world. Rather than me looking through a window to check for fire, perhaps I’m in the simulation with an avatar and me remembering to yell, “Samantha, peek through that window and see what it looks like in there,” would equate to my proof of competency.

With the exception of Ovation and its adoring throngs of presentation attendees, each of the training simulations reinforced the “you’re on your own” vibe too familiar to VR simulations. It was pretty clear that all of the simulations came derived from a single thought: “let’s do something with this curriculum in VR that would be too expensive in the real world.” That usually equates to putting the person in a situation and using signs and dialog boxes to push them through the same rote memory exercise found in reading, lectures, and videos.

I could just see the learning design specialist sitting there with the script to a video going, “Ok, so now we have to have the learner check for fire behind a closed door.”

Beyond the design elements, the actual interactions often lacked authenticity. I had a podium in front of me when delivering President Kennedy’s address. But what I really had were two controllers and nothing physical. One controller could play substitute for a clicker/laser pointer, but the other felt superfluous, which created a distraction. I wave, I pick up stuff, I hit the podium when I talk. I could perform none of those gestures without the back of my brain going, “no, that is just silly in this situation.”

So what I know of my presentation style wasn’t completely available within Ovation. I was locked down from the shoulders in a virtual straightjacket of sorts. It actually made me think of virtual paralysis. Everything below me was unreal and only the thoughts in my head and the voice coming out of my mouth was real. My body wasn’t real—not what I could see, and not what the VR experience placed as constraints on my real body. I could reach out to hit a podium, but I would not find one, which would ruin the illusion, so I remained rigid in my delivery.

That disconnect between reality and VR sits as the essence of the challenge that VR continues to face. If I’m outfitting myself with a number of pieces of kit to keep me safe, distinguishing between worn and fit for use visually is one thing. Holding a rope and tugging on it is another. But beyond that, picking things up with a controller doesn’t provide the hands with the right learned motion. Sure, we know how to use our hands so we can figure out the difference in the real world. But split-second translations after many repetitions may matter in safety situations. I don’t know if they do, but somebody needs to do that research.

Simulations also don’t reflect real-world timing. Once something is picked up, a tap puts it on the virtual body. Putting on a set of safety equipment is much harder than the simulation suggests, so people will need real-world experience with that because jeans and a t-shirt is not a set of robust safety garb. They will need to practice actually getting outfitted.

And then there is the time spent picking things up that were dropped because hey, controllers aren’t hands.

VR clearly creates value and offers immersive experiences. Organizations seeking to leverage VR’s unique capabilities need to balance expectations against the state of the technology in order to understand the clear trade-offs between cost and learning performance when comparing delivery approaches.

The Vive hardware experience

Settling into VR systems like the Vive Pro remain a bit of a theatrical experience. Tethered VR that includes standing and moving, requires more than one person just to get going. Think about it as putting on an elaborate costume before heading out on stage. A mask, prothetic ears perhaps, gloves or fake hands, and a tail that doubles as a safety harness. The problem is that non-theatrical people don’t know from getting ready for a performance and all that entails. VR isn’t as onerous but it is analogous.

Once strapped in and on, had I been left alone I would have fallen over the tether at least a couple of times. I might also have run into some furniture as I pierced the virtual wall that warned me that I was wandering off the virtual farm.

This multi-person need for engagement takes away some of the ROI by adding extra labor back into an equation. Yes, the training may prove more memorable to the subject, and the experience more holistic than a video, but neither a video nor a pamphlet requires labor once produced and distributed in order for the learner to acquire the content.

While displays continue to improve, I still found myself somewhat claustrophobic in the headset, especially during transitions. It created a feedback loop on body heat that made me sweat, and it did nothing for my hair. In addition, I often experienced blurs on the edges, some running ants depending on the selected UI patterns, and a couple of lost controller moments as the batteries reached their end of life.

Imagine in the real world how you would feel if all of a sudden your hand, visible out is space before you, refused to move. Now, because I had a crew helping me, they handed me a new controller and restored a sense of normalcy. Anyone using VR on their own would have had to take off the headset, fix the issue and then re-engage the experience starting with putting on the headset and adjusting it again to the right fit.

The Vive Focus Plus eliminated the tether, but the need for help remained for locating controllers and room safety. The overall experience was better from a wearability standpoint, but until we do a deeper dive, the differences in performance and available software are not yet clear.

The Vive software experience

Realtime rendering cannot compete with the photorealistic CGI effects that are now so common in the cinema. The problem is, we have come to expect everything to look like Avengers: Endgame or Alita: Battle Angel or you pick your favorite CGI extravaganza.

The renderings in these training experiences, while functional, looked antiquated. More and more, those being trained will come to that training with gaming experience. And while Fornite, Resident Evil or Final Fantasy can’t don’t match cinema-level renders, they do exceed these training experiences. People will compare their knowledge about what is possible —and they will likely find enterprise VR wanting.

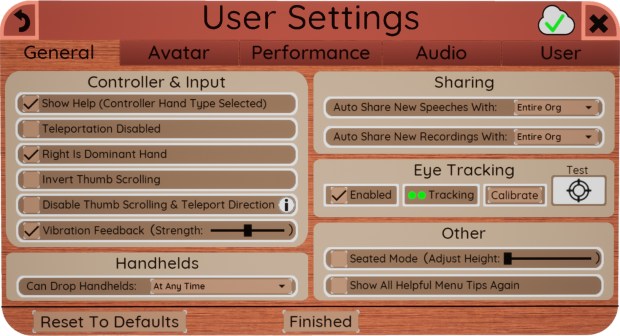

Beyond the rendering, pop-ups, preferences and other standard software features in all of the VR experiences felt like they were designed by people used to Windows or Mac development. The design thinking felt constrained to 2D metaphors, even though the controls occasionally slanted and cast shadows. The designers rarely took the opportunity to find a uniquely VR way to implement something like a dialog box.

There isn’t an answer to how to use VR-inspired elements for controls. Or it could be that we are in a long period of transition in which the 2D UI experience will dominate until designers figure out how to connect VR participants with alternative control metaphors. I do know that my life is not filled with dropdowns, dot-dot-dots, burger icons, dialog boxes and the like when I’m not looking at a screen.

It’s time to rethink VR controls. Why can’t alerts be haptic feedback that forces you to look at your wrist for the message? Um, say, like a smartwatch.

Why can’t data be displayed visually and explored as a physical thing (remember William Gibson’s Neuromancer)?

In VR, if we want the experience to echo the real world, we need to figure out how to set parameters that don’t require returning to 1980s computing for inspiration.

The VR Business Value Proposition

As I said at the onset, the value proposition for the Ovation experience aligned with my needs. I could personally, and easily identify why this experience could help me become a better presenter. The best value proposition is an obvious one to the customer.

Having worked in manufacturing for years, I gleaned the value of the training experiences as well but didn’t feel that even if I was working for one of the target companies that the training would be enough to instill full confidence in my ability to perform the same tasks in the real world. The simulations provided complex situations with some sense of what a real-world experience might look like, and offered guidance on how to behave. The issues of tactile feedback and false time, however, left me questioning the overall efficacy of the training scenarios.

That said, regardless of the development cost, all of the simulators compare favorable from the cost perspective to building real simulation situations, even if they require staffing to help people gear up. The real proof of benefit will come when a VR-trained person puts their VR-gained knowledge to work in a real situation and they perform as well or better than people trained in other ways.

Businesses continue to set aside funding to invest in VR experiments. And they continue to see value in training simulations, especially when it comes to safety or physical process. Even in the current state, VR will likely provide a better learning experience, improve retention and increase engagement. At least the first few times. It remains to be seen if the advantages of VR remain steady over multiple courses.

Vive for Business: Conclusion

There remains something magical about the immersive experience. The problem though is that current VR solutions keep reminding you that you aren’t somewhere else. VR headset users still find themselves in a piece of hardware that is heavy on the head and needs adjustment from time-to-time for comfort or visibility. The low-resolution worlds don’t match current expectations for what is possible from CGI.

The hardware continues to progress. Untethered experiences nearly match those of tethered headsets. But as with most computing, the real challenge comes in software—not just the quality of the operating platform, but the choice of metaphors and connection between user and experience. And in those later design choices, VR still requires work. The breakthrough in VR that will imbue it with a full sense of immersion continues to prove elusive, in the meantime, adequate, work-a-day solutions will predominate, but for enterprises, VR remains a tool, and isn’t just getting the job done the proof of value for all other tools?

Click here for more on VR from Serious Insights.

Leave a Reply